Researchers have developed a new coating for steam condenser pipes in an effort to find ways to make energy generation more efficient.

Scientists at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have recently developed a new coating made of fluorinated diamond-like carbon (F-DLC), a material that’s hydrophobic or water-repelling.

Today, many types of power generation are working on the stream cycle. Whether it is burning fossil fuels or through nuclear fission, the process uses an energy source to heat water in a boiler to produce steam, which is then channeled to spin a turbine to generate electricity. Then, the steam is collected in a condenser to reclaim the water to continue the cycle.

A New Carbon Coating to Improve the Efficiency of the Condenser Pipes

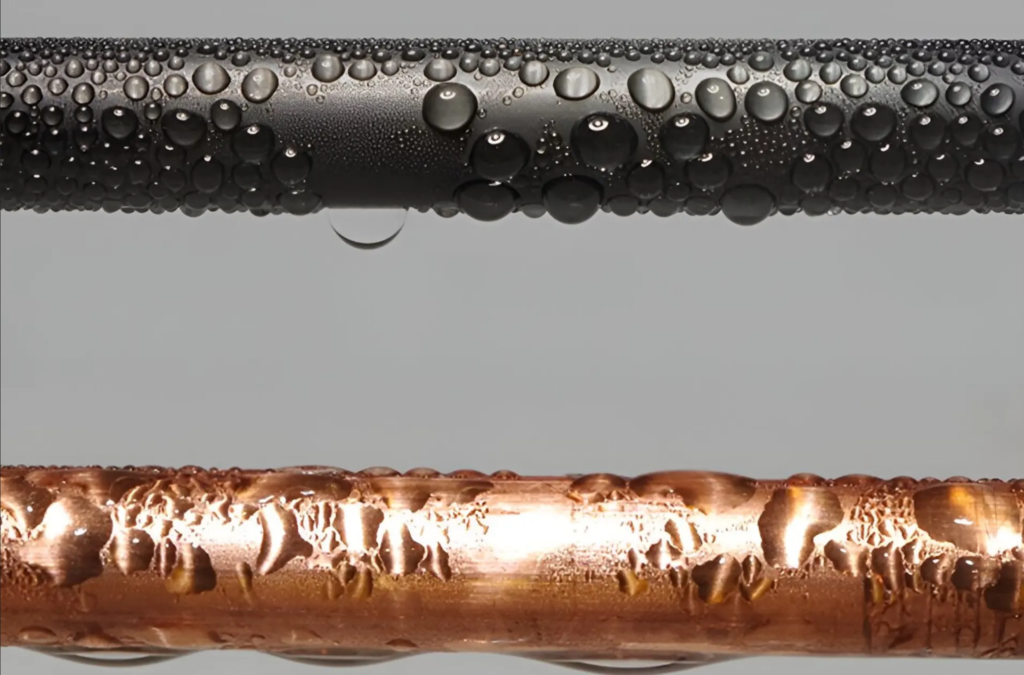

The new coating makes the steam condensed on the coated pipes no longer form a thin film. Instead, it will ball up into droplets much more easily, so it helps the steam run off faster, allowing more steam to come into contact with the pipe sooner.

The team has also proven that the coating boosted the pipe’s heat transfer properties 20 times, leading to an overall efficiency boost of 2%. According to researchers, if all coal and natural gas power plants were 2% more efficient, per year global CO2 emissions would drop by 460 tons, it would save 2 trillion gallons of cooling water, and it also would generate an extra 1,000 TWh of electricity.

As that’s more than Russia consumes in a year, this could potentially add more than Russia’s worth of extra power.

The Importance of A Sustainable Energy Cycle Structure

As weaning the world off fossil fuels will take some time, finding ways to make energy generation more efficient is still important.

Remarkably, F-DLC can coat pretty much any common metal, including copper, bronze, aluminum, and titanium. In addition, the coatings were durability-tested for 1,095 days and found that they maintained their function for the whole time. Not only that, they also did so after being scratched 5,000 times in an abrasion test.

There are still questions about how such a coating might be put into wide use, but it should start to make a difference if plants adopt it.

Article and Image Source: The Grainger College of Engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign